Watching an uncertain future

By Eric Chien

Hours before dawn on a mid-August morning, my crew and I started the truck and began the drive east back to the Brainerd office, ending our final project trip in North Dakota. Our departure was marked only by the sound of jumping gravel and the hushing of countless field crickets, whose mating calls had made the last ten mornings so raucously serene. “What is that?” Staring sleepily out of the window, one of the crew nodded toward the horizon. Natural gas flares burned hellishly on the horizon from the numerous oil platforms pumping night and day. That certainly wasn’t a new sight, but as my tired eyes drew away from the orange spotlights of the flare outs, a thin banner of blue-green light swept across the northern sky. Draped above the dark outline of North Dakota hill country that bounded the river valley we were driving through, the northern lights whispered quiet, but unmistakable light. The aurora, a symbol of wildness and the remote, stood in defiance against what many believe North Dakota is destined to become.

A drive across North Dakota highlights a somewhat paradoxical state identity. Just west of Fargo I saw squadrons of ducks and geese flying over the countless lakes of eastern North Dakota’s prairie pothole region. The state sits within the central flyway, arguably one of the continent’s last great wildlife migration routes. Many of the waterfowl that constitute that migration arise from the productive shallow water bodies and plentiful nesting cover of the eastern Great Plains. However, gazing down from the sky I often saw endless wheat fields, planted within feet of the water’s edge. More land in wheat production means less land for ducks. As of last year, North Dakota now produces more wheat than any other state in the country.

West of Dickinson, a group of pronghorn antelope grazed in a pasture. Behind only bison, pronghorn are the best embodiment of wide-open western landscapes. Yet, I also gazed on a horizon stabbed with oil wells. Signs of the wealth they were extracting from the ground emanated in every direction in the form of box stores, new pickup trucks and hastily built cookie-cutter houses. North Dakota now produces more oil than any other state in the country.

Buford is home to the confluence of two great American rivers: the Yellowstone and Missouri. A state historical society museum that recounts the arrival of Lewis and Clark sits at the meeting point. Running past the museum’s dirt parking lot is an irrigation canal that delivers water to dozens of growers in the river valley. As I drove along an irrigation canal in the Missouri River Valley, my passenger pointed out the window and said, “That used to be pasture, and that used to be crops.” A grower in this valley for several years, Ken had seen more than a fair share of land converted to oil infrastructure. From a place of rest on America’s greatest adventure to fertile agricultural land to the staging area for another oil pipeline; Buford has seen and been many things.

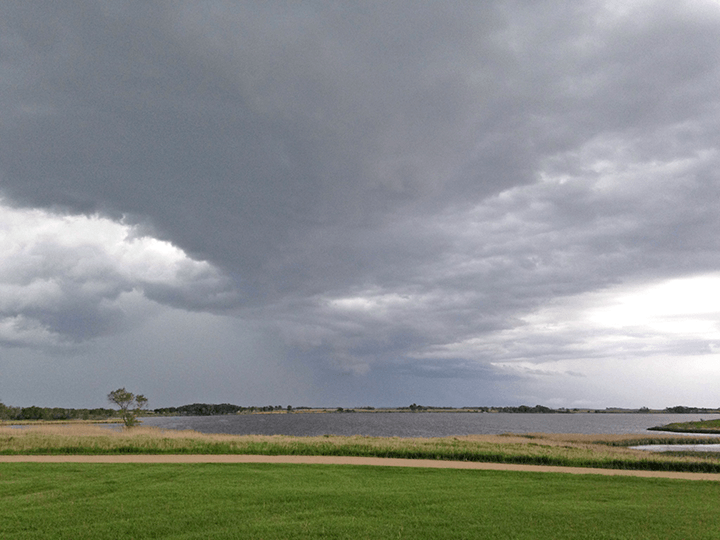

Working there less than three weeks, I have found North Dakota to be an intriguingly complex place. While inarguably diminished, wildlife stills clings to the land in conspicuous abundance. However, every view out the window also offers the sure signs of development incompatible with wildlife. The state sits at a precipice. There is a rush for oil and agriculture without a corresponding rush for conservation. If we can also find the merit in prospecting for our natural heritage, another corps crew may some night look out its tent windows, into the northern Dakota sky, and still see the aurora.