Not for the faint of heart

(Warning: this post contains some graphic photos)

By: Tamara Beal

There is no time of the year where bats get more attention than Halloween! A typical work day for us in late October was comprised of driving to sites where we had thermal cameras set-up and changing the batteries in the morning and then watching previously recorded video footage from these cameras in the afternoon. With daylight savings time shortening our evening daylight hours and November welcoming in some colder temperatures, we took full advantage of our work hours spent cozying up to our computers watching for bats entering rock faces. Below are some photos of what is believed to be a bat flying from the right side of the screen to the left.

Although bats were the main attraction of our video monitoring, we tried to identify all nocturnal heat signatures picked up by the thermal cameras. Below are some photos of raccoons caught on camera strolling up the hill.

Our bat work officially wrapped up on November 10th and our new work studying chronic wasting disease in white tailed deer began on November 13th. To best utilize the four of us “bats and bucks” crew members, the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) split us up: Amy and I were sent together to work at a DNR office in northeast Iowa, while Amanda and Inga were sent separately to DNR offices in southwest Iowa.

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a disease that affects the brain and is highly contagious within members of the deer family (deer, reindeer, moose, and elk). It is caused by an abnormal protein, called a prion that causes neurons in the brain to degenerate, essentially eating away portions of the brain. It is spread by direct and indirect contact with bodily fluids and is always fatal.

As of October this year, 18 positive cases for CWD had been verified within Iowa, with all 18 located in northeast Iowa. The most affective way to check for CWD is to remove the lymph nodes and send them to a lab to test for the presence of the CWD causing prion.

Currently, in bow hunting season, the number of hunters that we could reach out to and ask for permission to take lymph node samples are low. Instead, we get most of our samples in November from roadkills and taxidermists. On the right is a picture of me on the side of a road cutting the lymph nodes out of a doe that most likely got hit by a car.

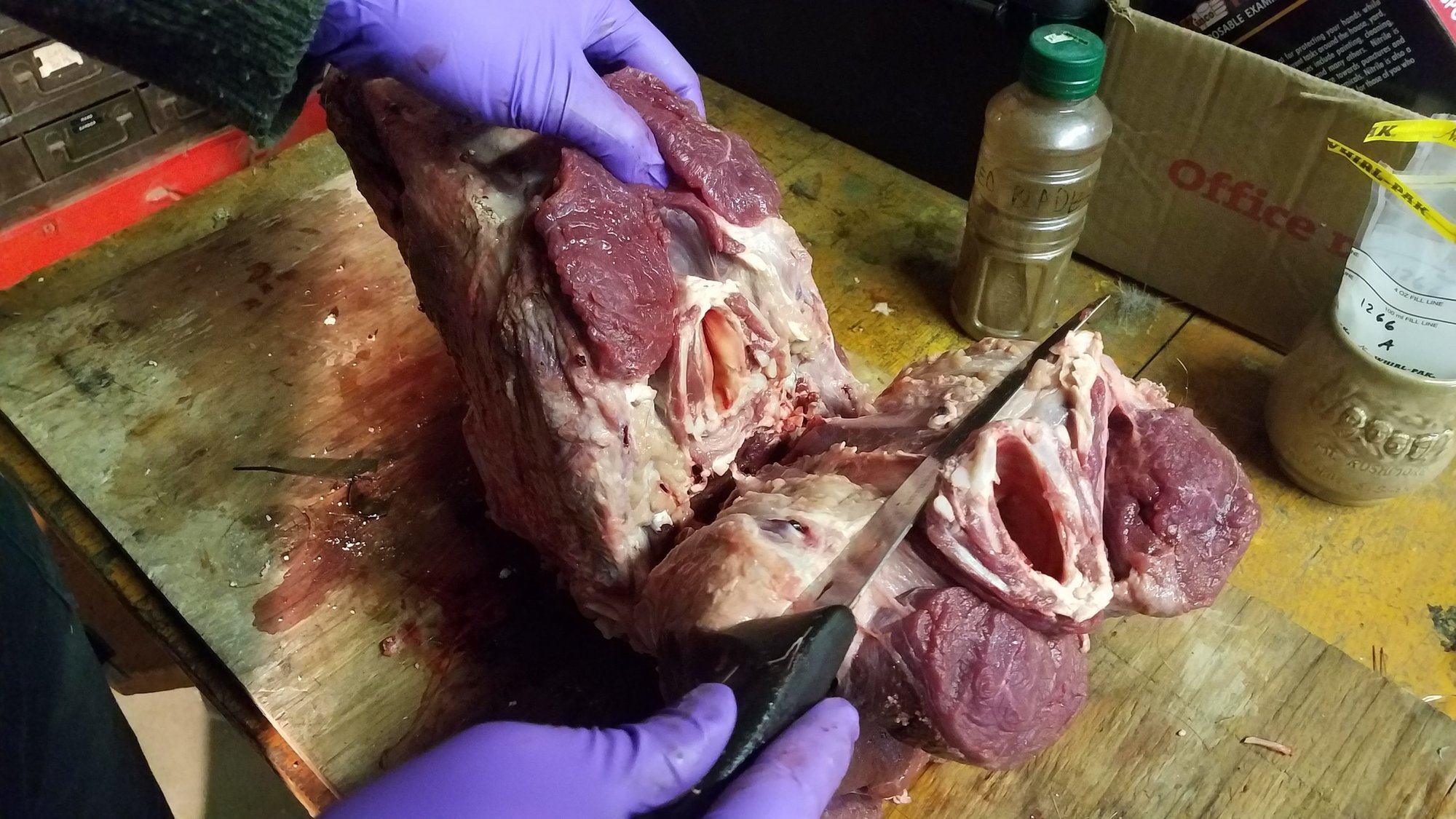

Before we gained experience cutting into roadkill deer in the field, we initially learned how to take lymph node samples on heads we received from taxidermists after the hide had been removed for mounting (not for the faint of heart).

The simplest way to access the lymph nodes is to slice into the deer an inch back from the jaw bone and then make an incision into the back of the throat (bottom left). The lymph nodes have a tougher consistency than the other tissue around it, usually making them pretty easy to differentiate (bottom right).

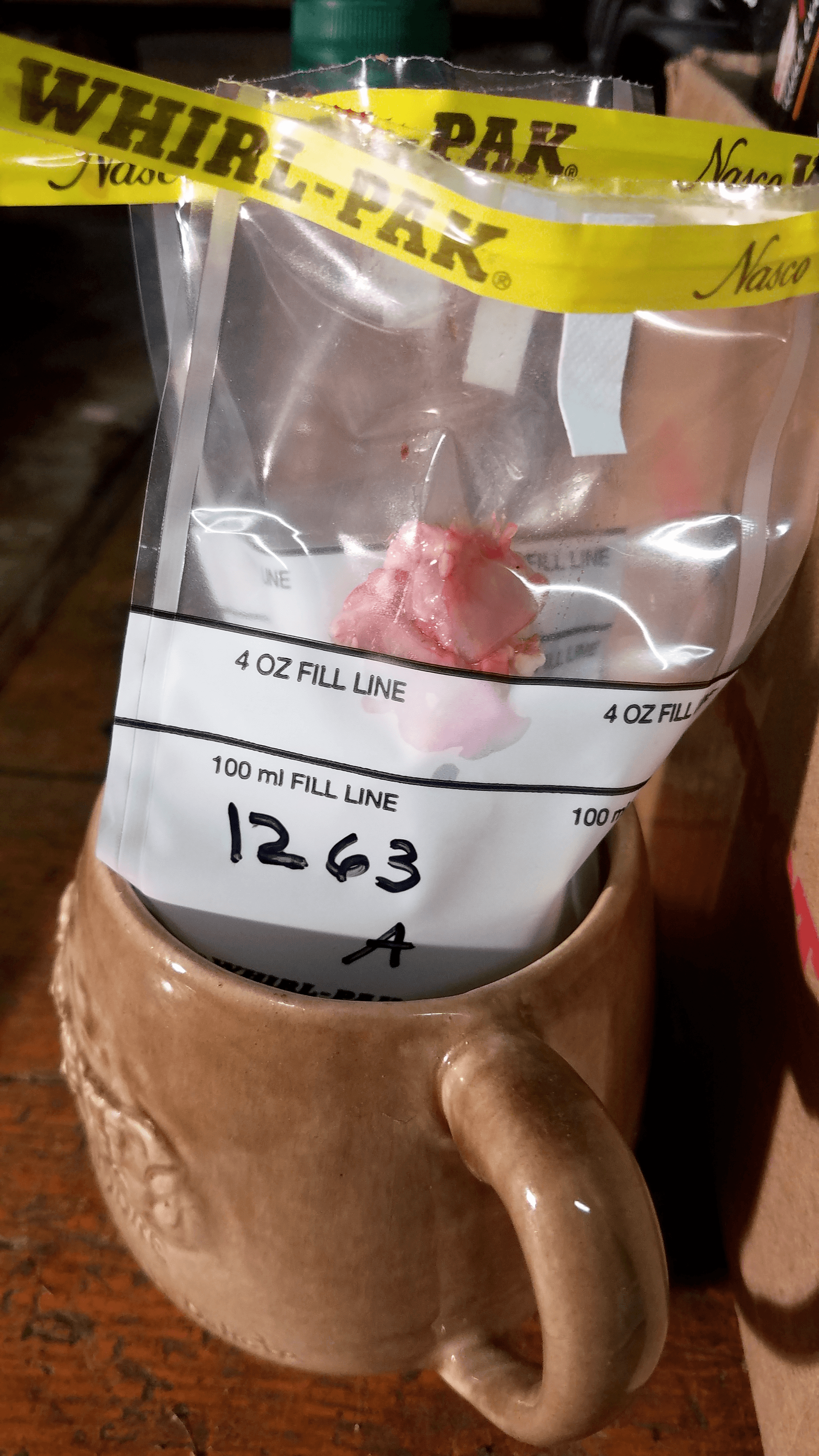

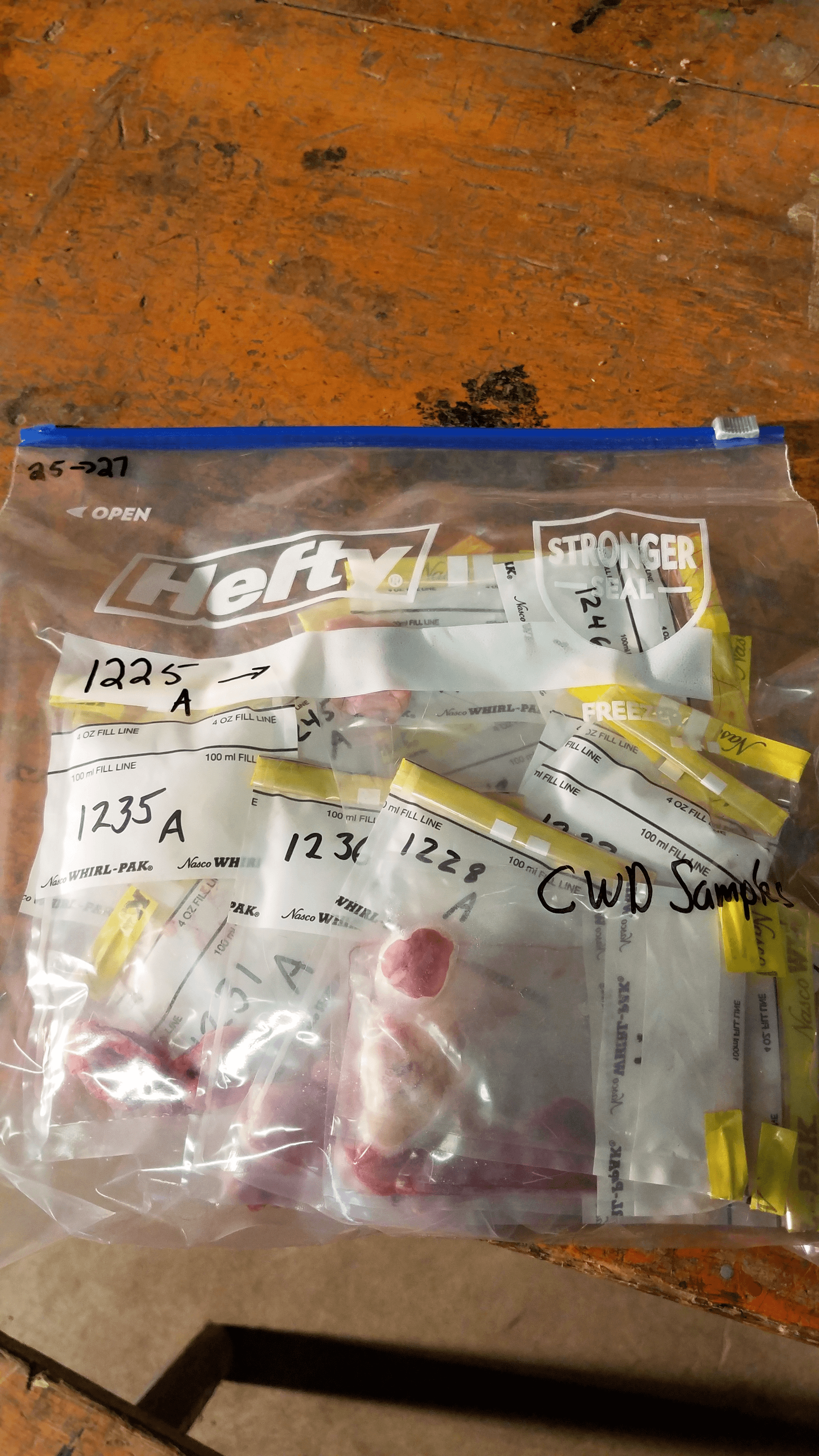

For every sample specific information must be recorded on a sheet, such as if the deer was adult or a yearling (fawns are not sampled), sex of the deer, where it died, whether it was a roadkill or a hunter’s kill, and if it was a hunter’s kill, their name and phone number. Once the lymph node samples are taken, they are designated arbitrarily A and B and separated into zip lock bags, labeled, and stored temporarily in a freezer (bottom left). After a sheet is filled up (25 deer have been sampled), the A samples are collected together to be sent to the Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory in Ames, Iowa (bottom center and right), while we keep the B samples as back-ups. Results of this testing is made known to the public, usually in less than 10 days.

Although there is no current evidence of CWD being able to be contracted by humans, the DNR highly recommends against consuming any meat of infected deer and suggests keeping deer kills separate from each other and clearly labeled.

With only one month left in my Conservation Corps term, next month will be my last blog post as a Wildlife Studies Crew member. Stay tuned for a update on our CWD work in light of the craziness that will ensue during December shotgun hunting seasons. I am sure to have some good stories of interactions with hunters, as well as a final update on the “bats and bucks” plans for life after Conservation Corps!