Finding wilderness in the city

by Gina Hatch, visitor services intern/ AmeriCorps member with Minnesota Valley National Wildlife Refuge through Conservation Corps’ Individual Placement program

Refuge staff enjoy views of the Minnesota River valley. Gina Hatch/USFWS.

For most of my life growing up in New York City, city and nature felt diametrically opposed. I was pretty sure that my hometown of glass skyscrapers and dark subway tunnels was a place where nature went to die. The city parks where I enjoyed respites of fresh air and billowy trees were comforting but usually seemed a little forlorn to me. And they felt like poor stand-ins for the bigger swathes of wilderness where I would have rather been.

To make a long story very short: a combination of ecology research, biology classes, and work in environmental education throughout college eventually changed my perspective on the city. These experiences rewired my brain so that suddenly I was seeing and understanding so much more about the hidden wild lives all around me, even in the Big Apple. The city became its own special ecosystem to me.

The “weeds” growing up in sidewalk cracks were no longer withering vestiges of a green world subsumed by concrete; I started to see them as innovative pioneers learning how to adapt to life in the concrete jungle! Perhaps they were like the plants I had read about in my evolution textbook, evolving rapidly to drop their seeds in place instead of dispersing them, so that they would land on the tiny threads of soil from which the plants themselves had grown rather than being carried to some impenetrable patch of concrete elsewhere. The towering buildings obscuring the sun feel imposing, yes, but unknown to millions of New Yorkers walking beneath them, those skyscrapers are supporting one of the world’s largest peregrine falcon populations, providing powerful currents of warm air on which to soar and ideal perches from which to dive for pigeon prey. Right under our noses (or over our heads) the cities and suburbs are full of examples of wildlife reclaiming homes alongside us and making fascinating adaptations to survive and thrive where no one is expecting them.

In my placement site at Minnesota Valley National Wildlife Refuge, we tell people that we are the wilderness in their backyard and their gateway to nature. Located right on the periphery of the Twin Cities, most people probably take these tag lines to mean that we are an easy escape from the city—and indeed we are. But as an urban wildlife refuge, so powerfully situated next to more than 3.5 million metro residents, we can be more than just a brief escape into green; we can be a force uniting two worlds that really shouldn’t feel so separate in the first place. For visitors who can access the Refuge on a whim, just as for visitors who can only get here on occasion—and even visitors who never thought of the Refuge as a resource available to them—we can provide experiences that change the way they engage with nature in their own neighborhoods, local parks, and plain old city streets.

When I started my service at the Minnesota Valley, I was thrilled to find myself at a place with a mission so personally meaningful to me. Armed with my own unlikely tale of urban nature discovery, I was excited to make a dent in this work. I was assigned the task of creating my own short ranger talk to deliver regularly to Refuge visitors, on any topic of my choosing so long as it was carefully crafted to be engaging and to utilize interpretive strategies that would accommodate visitors with diverse interests. I quickly settled on a theme of urban wildlife. I got to work eagerly drawing on the bits of my ecology classes that I could remember and collecting examples of wildlife that had made it big in the city. I was ready to explain and prove that the Venn diagrams of city and nature overlapped, starting right there at the Refuge.

But as I spent time talking to families and small groups by our display of bird feeders or out on our observation deck, I noticed that people—and kids most especially—wanted to know much more urgently about the things chirping and buzzing and swaying right in front of them. They come to the Refuge to enjoy using their senses—to see and hear and smell and touch. Whatever surprising factoids I could share about how urban squirrels’ brain were larger than that of their rural counterparts, or how raccoons learned to open jars, were probably not going to leave as deep an impression as the experience of looking through a pair of binoculars for the first time or seeing a thread of fishing line woven into an oriole’s nest. And moreover, learning these facts was not going to give people the tools to keep making their own observations after they left the Refuge.

I started loosening my grip on my scripted examples and thinking more about the immediate. Over time my rehearsed talks morphed into more casual chats, responding to the whims of my audience and focusing more on learning how to take in the things in front of us. After sitting in on a couple of birding workshops offered at the Refuge, I was inspired to incorporate some sensory exercises into my talks and walks, for instance having visitors practice focusing their listening in the four cardinal directions. I still keep looking for opportunities to talk about urban wildlife but try to link those themes more directly to cues around us, like an airplane flying overhead or something a visitor brings up themselves. My hope with these talks now is that visitors will leave just a little more primed and eager to keep seeing some of what they saw with us, and that as a result, the hue of the Refuge’s green will feel just a little less different from the city’s grey.

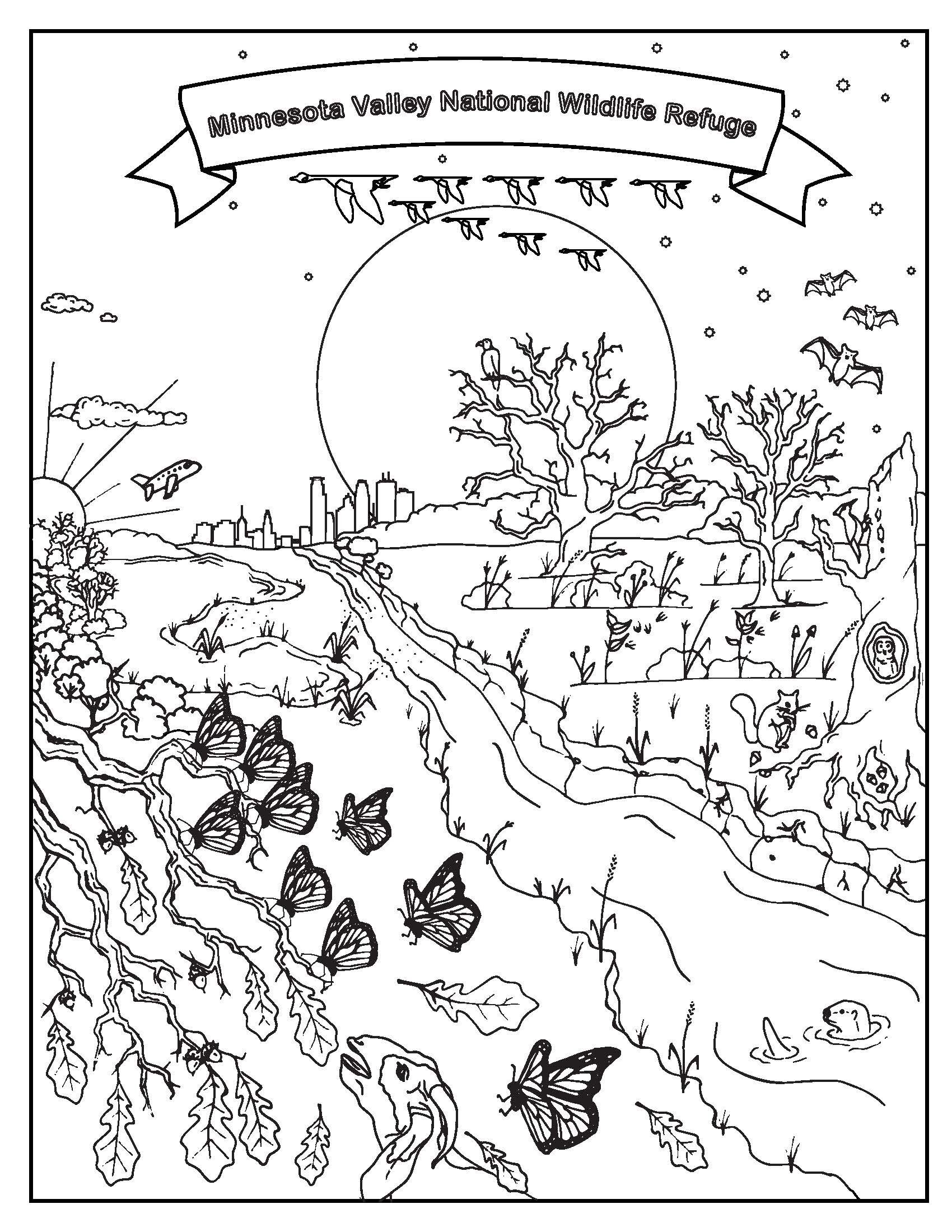

A poster created for Minnesota Valley’s “Wildlife in the City” festival last fall.

We can’t guarantee visitors the chance to spot charismatic creatures each time they come to Minnesota Valley. But the Refuge is a perfect place to demonstrate how exploring our surroundings with an open mind and open senses often leads us to discover things we could easily overlook. Personally, I would choose a walk through a refuge or a park over a visit to a zoo any day because the former requires me to tune up my senses, shift my focus, and enjoy the thrill of a search. It’s an immersive process that rallies my full body. When I find myself back in a maze of buildings and concrete an hour later, I’m still in the habit of directing my focus to the varied textures of bark or the flutters of wings—more occasional, but certainly still there. And when I do get the chance to appreciate wildlife in these urban contexts, or encounter a favorite plant I didn’t think was anywhere near my light rail stop, it’s all the more gratifying and reassuring.

There’s more value to finding nature in our cities and suburbs than just entertainment and fascination, however. If wildlife surrounds us in our neighborhoods, the implication is that we can be stewards of the environment on our home turf and in small everyday kinds of ways. Our public lands and wildernesses are critical to conservation but are under constant threat and still woefully inaccessible to many. Finding nature where we live empowers us to feel connected every day to a global ecosystem that registers all of our choices and actions in the city, in the wilderness, and everywhere in between.