Individual Placement Spotlight Series: Adriene Matthews

By Jesse Wolk, Utility Mapping Specialist Individual Placement / AmeriCorps Member placed at Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Parks and Trails

X: The Carrot

The Individual Placement (I.P.) Spotlight Blog is a series of interviews between Jesse Wolk and his fellow full-term I.P. members. The goal of the series is to highlight their unique positions, projects, and backgrounds while simultaneously reflecting on their service term in the context of the Natural Resources career field in Minnesota. In the tenth edition of the series, The Carrot, the spotlight is shifted to our Agricultural Outreach Specialist – Adriene Matthews!

The way land has been “owned” has shifted throughout human history. From feudalism to subdivisions to collective land ownership, the way that humans claim, or share, the ground that they trod upon has a complex and bloody history. Today, in the United States, there are essentially two categories of land ownership: Public or Private. While this article will not focus on the story of how these lands came to “exist”, it is acknowledged that these lands did not suddenly appear in a vacuum before they were bought from Native Peoples largely through deception and lies. All land was indigenous land, it just had to be stolen. Go to Native-Peoples.ca to find out what peoples traditionally lived, and live, in your neck of the woods.

Back to our land categorization, public lands are those owned and managed by a governing body like a federal, state, county, or municipal agency. These lands make up approximately 33% of all land in the United States, much of it in the western half of the United States. When we bring Minnesota into the fold, it is relatively average. Approximately 27% of Minnesota’s land is public. This ranks the state 17th in total percentage of public land. Accounting for the 2% sliver of tribal lands, the remainder of land in the state is private. This 70% majority is owned by individuals and corporations. Furthermore, most of this private land is used for agriculture. In fact, this agricultural chunk is large enough that covers half of the state in area. Follow this link from the National Land Cover Database (2019) to visualize that. According to the USDA in 2023, the gigantic presence of agriculture made Minnesota the sixth most agriculturally productive state in the nation.

While 21st century farming is contained within a private border, its impacts are not and unlike clear-cutting or strip-mining, the environmental degradation of agriculture is much harder to see. The first big issue is that excess nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus, are threatening our water quality. This “overload” is largely from crop fertilizers and manure runoff and is making certain Minnesotan’s drinking water undrinkable, 25% of our lakes unswimmable, and quite a few of our streams uninhabitable for aquatic life. Secondly, accelerating topsoil loss continues to outpace topsoil build-up, endangering a non-renewable supply of the resource that we use to feed the nation. Our rich topsoil was formed over thousands of years through the nutrient deposition from the glaciers and tallgrass prairies that came in their stead. This past July it was estimated that 35±11% of nutritionally dependent topsoil is projected to have been lost in the Corn Belt since the plowing of the prairie. It is expected to only get worse. The situation is dire, and currently, is somewhat unregulated.

As someone who isn’t a farmer, the future feels bleak. A natural reaction to what I just wrote would be anger. Luckily, for Adriene Matthews, the I.P. Program’s Agricultural Outreach Specialist, this wasn’t the case when she started her service term. Growing up in densely populated southern New Jersey, Adriene says that she was disconnected from farmers and agriculture. She would grow up hearing her mother talk about supporting local farmers through consumptive choice, but she never learned much about agriculture throughout her education. She came into this experience with a blank slate. After a year of serving with the Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD) in Cottonwood Minnesota, she told me that she learned the challenges that farmers face when attempting to become better environmental stewards. Through her experience, she gained professional nuance.

Rewinding a little, after graduating high school, Adriene became a medical assistant, got a car, and began to expand her breadth of experiences. After visiting Vermont and volunteering for the Fish and Wildlife Department back in New Jersey, she was inspired by conservation projects and the people that work on them. After six years working in healthcare, she realized that this was not the path she wanted to continue down and began an online program in Wildlife Conservation from Unity College. At around the same time that she realized her career goals, she got an email from CCMI on Handshake asking her to apply to the Agricultural Outreach Position. She applied to the position to learn more about the intersection between agriculture and conservation and soon, found herself packing her bags to move to rural Minnesota and to start serving with an SWCD!

Soil and Water Conservation Districts are agencies that are operated by a board of elected officials on the county level. They function, “to conserve soil, water, and related natural resources on private land.” Essentially, they act to incentivize private landowners, which are mainly farmers in Adriene’s district, to incorporate sustainable practices like cover crops or decreased tillage into their farm.

When I first learned about SWCDs, I thought it was as simple as an agency that dangles a grant-carrot to get the farmers walking in the right direction instead of whacking them in the behind with a regulatory-stick. Adriene wants to make it clear that it is not that simple. As she rightfully corrected me, SWCDs do more than just dangle a carrot. First, while they do dangle the carrot to all, they only offer the carrot to those who want it. Many farmers have been farming the way that generations before them have. Rejecting that could result in social isolation from their community. Secondly, if they shift their practices, their already small profit-margin may, or may not, decrease from the cost of acquiring new equipment and learning a new method. They might lose money, especially at the beginning. Finally, they may want to incorporate the practices that I have mentioned but they might not even be able to. Adriene told me this was the case for many farmers. For example, they may not be able to afford the upfront cost of the equipment, or the soil that they have is too hard for a no-till drill, or they are renters who are at the will of their landlord.

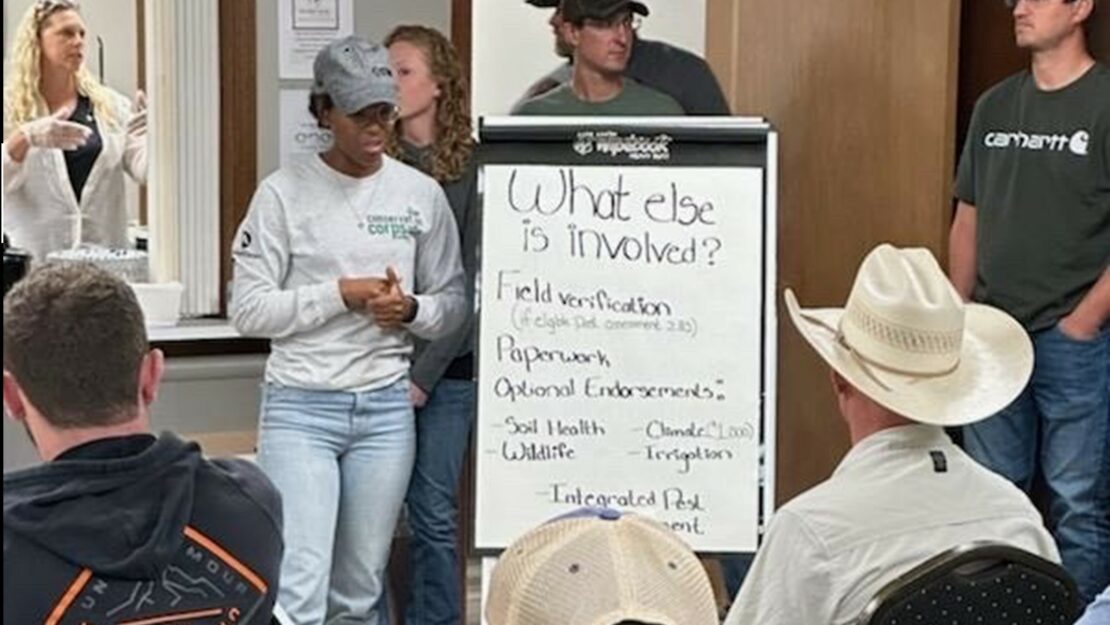

If they can overcome all these obstacles, and take initiative to grab that carrot, then SWCDs offer farmers trainings, mentorships, and site visits to address their individual needs and work to find a practical solution that works for them. Adriene goes on these site visits alongside SWCD technicians to speak with these landowners. She also travels to properties with Minnesota Department of Agriculture Water Certification Specialists to do water quality testing. Adriene has never gone on one of these site visits alone because she has been learning. A lot. Water quality monitoring, farming jargon, rural culture, and challenges facing agriculture are all topics that Adriene has quickly been picking up on to become a better communicator. When she’s not doing site visits, Adriene has also built a new website for the SWCD that she operates in, planted around 1,000 trees with SWCD Technicians and a CCMI field crew in May, and has done data management in ArcMap.

Adriene says that now that she’s been in the position for ten months, she can have conversations with landowners comfortably and has given herself space to not know everything. She has enjoyed the variety that the position has offered her and has gotten to know what she does, and doesn’t, like in a conservation position. She’s also had plenty of time for professional development. The flexible nature of the I.P. program has allowed her to take a ton of free trainings on topics like cover crops and soil health. She’s also used her training budget to take a grant writing workshop, received trainings on horticulture and pollinator habitat development, and became a certified Tree Inspector.

Even though she has developed personally and professionally, she still feels like she has more room to grow and is planning on staying in the position for another term. Next year, she plans to take what she has learned to become more independent and hands-on. She hopes she can use new skills to lead conversations and connect landowners to the right resources. Impressively, Adriene is still working towards her bachelor’s degree and following next term, is hoping to enter a position in Environmental Education where she can inspire children to take the amazing path that she’s followed.

As I painstakingly broke down in the beginning, the largest plurality of land ownership in Minnesota is private farmland. It is critical to offer these landowners, who have a huge impact on the health of our ecosystems, are offered a positive means of changing their methods. With regards to private land-use, policies and regulations are critical. However, they become obtuse obstacles that are easily avoided through litigatory cunning. For easy examples, see how for decades unmitigated non-point pollution from unsustainable agricultural practices has been one of the leading causes in destroying bodies of water like Lake Erie and the Gulf of Mexico.

To be clear, it’s not like farmers aren’t attempting to change their ways. Many farmers are using a less impactful plow on the soil than they were 50 years ago and soil tilling is becoming less common. Also, it’s not just farmers that are polluting our water! Urban stormwater systems, lawns, and other industries are also contributing to water quality declination. However, agriculture is the primary source. If farmers, and other landowners, can be shown that bottom line methods will lead to a bottoming-out of their businesses, then maybe systematic change can happen.

People doing work like Adriene’s will help farmers take the methodologically brave, financially risky, and potentially isolating step of changing their businesses and grabbing the carrot. Ultimately, it is farmers that will lead the change that our future needs. As a society, we should use every tool that we have help them do so.

Thanks for reading and catch you in a few weeks!

– Jesse

Jesse Wolk (he/him) is currently a Utility Mapping Specialist in the Individual Placement Program who is serving for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources’ Division of Parks and Trails.