Minnesota’s fiery geological secret

By Jake Richards, IT Specialist Individual Placement / AmeriCorps Member placed at Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Parks and Trails

Often when people think of Minnesota’s geologic history, the first thing that comes to mind is the influence of various forms of water. Lakes, rivers, glaciers, and even an ancient sea all had large impacts on the landscape we see within the state today. However, surprisingly to many due to the evidence of its presence being much more obscure than somewhere such as Hawaii, the impact of volcanic and fault line activity is extensive.

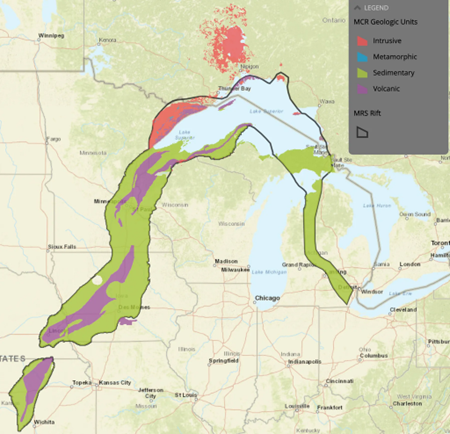

The story of Minnesota’s fiery past starts 1.1 billion years ago, when the planet looked incredibly different than it does today. Multi-cell organisms had just evolved and the first plants that look even somewhat like something we would recognize today were starting to appear. The land we now call North America was being ripped apart, and in the 1200 mi long rift that was being created was lifting molten rock from the Earth’s core and spewing it across the surface over a large section of the continent. This rift (see below) spread in a vaguely “n” shape with its lower left end in modern day Kansas, the peak in southern Ontario on the shores of present-day Lake Superior, and its lower right end extending as far south as Ohio.

This rift did eventually fail in its mission to tear the continent apart and is currently the deepest known rift on Earth to not create an ocean (which I personally am very thankful for). However, its intense activity created evidence of geologic activity of many different forms stretching across Minnesota’s eastern flank. The fault created the massive basin that Lake Superior itself sits on, the basalt, gabbro, and other igneous rock formations that dot the landscape from Interstate State Park near the Twin Cities all the way up to Grand Marais, and even some of the minerals that make up the expansive ore deposits in the Upper Great Lakes region. Once the rift activity died down and the landscape cooled, Minnesota became much less volcanic and seismically active. This allowed for the sweeping changes caused by water to occur and dominate the landscape over the coming billion years. However, if you find yourself anywhere along the St. Croix River Valley or North Shore of Lake Superior and start to notice the hard gray rocks (see below) surrounding you, take a moment to think about the hidden history of fire from the earth that occurred right where you’re standing to create them.

Sources: