“Natural Stream Design” Changes River, Crew Members’ Perspectives

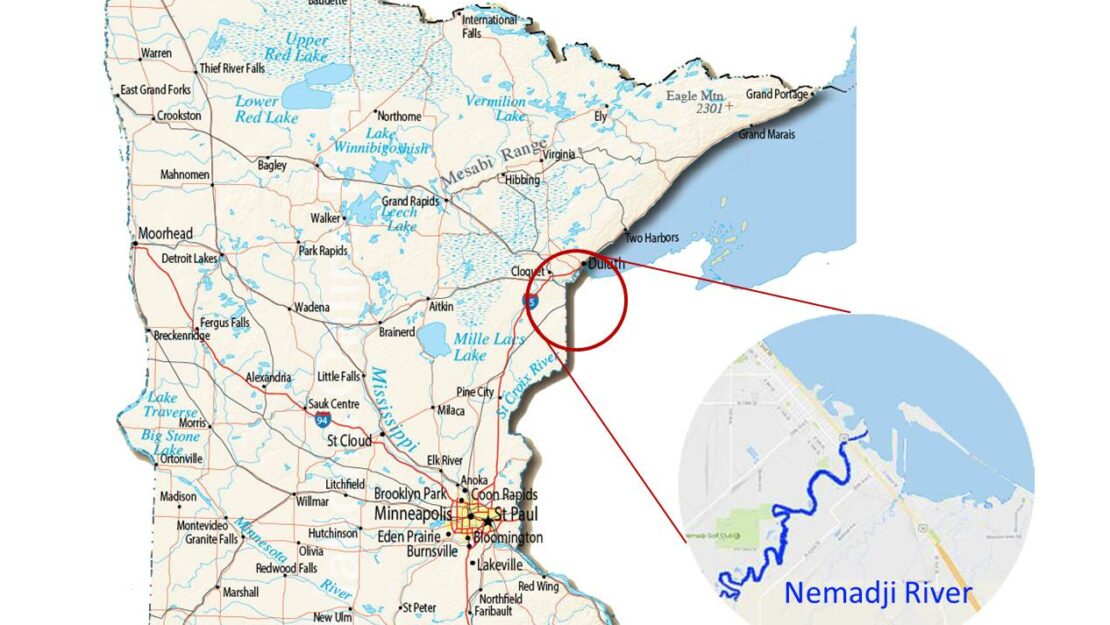

The meandering Nemadji River flows through northeastern Minnesota, crosses into Wisconsin and empties into Lake Superior, at a point just a few miles south of the city of Superior. It took a major hit in 1992, when a Burlington Northern train derailed and dumped 30,000 gallons of highly toxic aromatic hydrocarbons into its waters, to the great detriment of its fish and wildlife. And thanks to glacial melting thousands of years earlier, it was also the recipient of tons of red clay silt that its flowing waters would carry to Lake Superior and create havoc for ever-larger ships that, in much more recent times, needed deeper water to avoid hitting bottom. Dredging was expensive – all the red clay silt made it more so – and the work interfered with the smooth flow of commerce at the port.

A collaboration between Conservation Corps Minnesota & Iowa (CCMI), the U.S. Army Corps and Engineers and the Carlton County Soil and Water District (SWCD) used science, engineering and some brawn to control the silt, but the bigger success may have been the impression to project made on the CCMI crew.

A circa-1970 attempt to fix the Nemadji was to build red clay dams that stopped the water flow so the silt in the water could drop to the bottom of several man-made ponds. This worked until it didn’t: Over time, the dams failed, the water flowed and the red clay silt made its way to Lake Superior.

Adding to the Nemadji’s problems was a watershed that had been heavily logged, leaving little there to control erosion. Its red clay banks were unstable, and fast-flowing water made it difficult for any plantings to take root. The red clay silt reduced water quality for drinking and recreation and restricted light penetration needed for any aquatic plantings trying to get established.

The objective of the 2016 project was an enduring river repair. Working from a “Natural Stream Design” that uses science and engineering to write a blueprint to manage red clay silt and “reboot” the river to make it behave in a less destructive way, the SWCD and Army Corps of Engineers first created meanders to reduce the energy in the water. New food plains also gave high water somewhere to go, instead of confining its flow to a narrow area that would cause faster water movement that would agitate sediment and increase erosion.

The CCMI crew did the heavy lifting, transporting and placing rocks on the river banks to reduce erosion and building “stream vanes” that directed water flow away from the banks.

Natalya Walker led that five-person crew and remarked on the benefits of working with the engineers.

“We hadn’t worked with engineers before, and they provided a great and refreshing new perspective on how to approach management strategies,” she said. “We were able to see the calculations that went into the stream bed design and the importance of the way we placed the rocks. We received a crash course in fluid dynamics and erosion control. That experience was hands-down memorable.”

She also corroborated a life lesson: Any honest work done well is honorable work.

“Something else we enjoyed was the local soils. It was an environment we had never worked in before,” she continued. “We realized that even though the work we do is ‘manual labor,’ it’s important, impactful work.”

Finally, she and her crew learned something they can take beyond their time with CCMI.

“We can never approach two projects the same way,” she noted. “Each scenario requires its own, individualized method. As we worked in multiple areas, this concept became more and the more clear as we laid rock in each area very differently in an attempt to receive the same outcome; erosion control through directed water flow.”

In the end, the CCMI crew left a river in better shape than the one they found. It could be said the river did the same for them.