Fall into hibernation

By: Tamara Beal

Fall is officially in full swing! And that means it is migration season for many animals ranging from the smallest of insects, to birds of every size and color and especially our main attraction…bats!

Over the last month, many changes in the bat project have occurred. Mist netting finished up with another handful of Northern Long Eared bats being radio tagged. And lucky for us, we were able to catch a species that had thus far alluded us, the tri-colored bat (right)!

Alongside daytime ground tracking, Copperhead biologists have been up in the airplane checking where the radio tagged bats’ nightly wanderings take them. Sometimes the bats would not move at all, whereas other times the plane might find them miles from where they were caught the night before. Below are some views of Iowa from the cockpit!

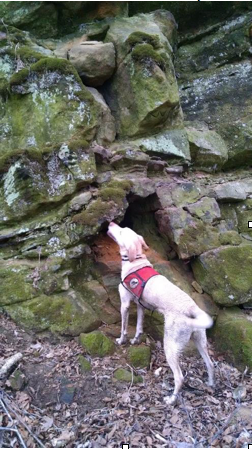

In preparation for migration season, we switched over from mostly night work with Copperhead Consulting, to some daytime work days with Josh Otten, a biologist from Stantec. Last winter, the Department of Natural Resources decided to try a new technique to determine where Northern Long Eared bats were hibernating. Conservation canines is a organization that specifically trains dogs for conservation related tasks. In a similar fashion that a police dog is trained to track down criminals by scent, dogs can also be trained on the scent of specific animals. In this picture, a Conservation canine, Lily, can be seen sniffing at a particular rock outcropping, identifying it as a likely hibernation roost for Northern Long Eared bats.

Based on the locations that Lily and other Conservation dogs identified, Josh picked hibernaculum at four parks to put up thermal and infrared cameras. Each park began with two full set-ups which included two thermal cameras, two infrared cameras, two infrared lights, two camera stands, two screens for the infrared cameras, two raspberry pis (data storage), two 35 pound batteries, two plastic tubes to protect the wires, and finally two big tubs to keep everything waterproof (left). All of that totaling over 200 pounds of equipment and over $10,000 per site.

But figuring out what equipment was needed for each site was only the beginning of the adventure. The real fun was getting all the gear to these sometimes remote hibernaculum sites. All of the “Bats and Bucks” crew can be seen to the right struggling to cross the Iowa River on the way to investigate one of our first hibernacula camera set-ups. With some of the walks into these sites being over a mile on uneven terrain, we are lucky to be working in such beautiful locations.

Pictured to the left is a closer look at the controlled chaos that is required for one of these camera set-ups. The picture in the center gives an example of one of our thermal and infrared camera systems once it is all set-up. And pictured to the right is an example of a rock face the cameras are trained on, believed to be a long eared bat hibernacula.

A few nights, we even got to test out what the cameras were seeing by wearing night vision goggles. For an hour we would scan a rock face hoping to catch a bat emerging from between splits in the rock (Inga- left). The goggles were not exactly comfortable to wear with straps around each side of the head, but being able to see in the dark was worth the discomfort (center). While conducting the emergence count, we also used an Echo Meter app to identify the bat calls in the area and determine if any happened to be Northern Long Eared (right).

No field work would be complete without unexpected wildlife lessons! Lucky for the four of us, Josh knows a great deal about snakes and gave us a lesson on any snakes we came across. Some of these included an adult black rat snake (left), a timber rattle snake (center), and a young of the year black rat snake (Tamara- right).

Last week we said good bye to our Copperhead friends as their part of the project had come to a close. Although we are still doing a small bit of day tracking, most of our time is taken up by changing batteries at the four hibernaculum sites. The newest development for our work, however, is beginning the data analysis of the footage recorded at these sites, manually scanning for any signs of life; bat or otherwise. Stay tuned for an update on the results of the thermal camera video recordings and the initiation of our work with white tailed deer and chronic wasting disease in mid-November.

Amy looking fierce and victorious with a yeti battery in front of a grand maple tree.