Monitoring a Bluebird Nestbox Trail

By Clara Brown, Fort Snelling Visitor Services Specialist Individual Placement / AmeriCorps Member placed at Fort Snelling State Park, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

The Eastern Bluebird arrives in Minnesota between late February and Mid-May and their arrival is a sign that spring has sprung. The males are stunning blue above with rusty orange on the throat/breast. They are fairly common in Minnesota nowadays but in the early 20th century introduced species, habitat loss, and pesticides caused alarming population declines.

Bluebirds live in open grasslands surrounded by forest. They are secondary cavity-nesters meaning that they use cavities created naturally or by other birds. The introduction of invasive House Sparrows and European Starlings caused problems for bluebirds because they also nest in cavities and are much more aggressive.

One major contribution to the recovery of the Eastern Bluebird was/is a nationwide effort to build and maintain bluebird boxes. If the boxes are designed properly they can prevent Starlings and House Sparrows from using them which creates cavities that are more available to bluebirds.

There are many different types of nestboxes but two of the most common are Gilbertson boxes (4 inch diameter PVC pipe with a wooden roof) and Peterson boxes (¾ to 1 inch thick wood). All boxes should have a 1 ½ inch round hole which allows bluebirds in but keeps starlings out. All boxes have some sort of access door or system so that monitors can open the boxes and check on the nests/birds.

When setting up a trail it is important to ensure that the boxes are placed in ideal bluebird habitat. They should be 50-200 feet away from the forest edge to prevent forest species from using them. Since tree swallows and chickadees generally also use bluebird boxes they are set up in pairs. Having two boxes roughly 5-15 feet apart allows the bluebirds to use one box while the other species will use the other. Pairs of boxes should be at least 100-150 yards from other pairs to prevent competition between bluebirds.

Once the boxes are set up they need to be monitored. During the nesting season boxes should be checked once a week. Carefully open the box, observe what is inside, and close the box.

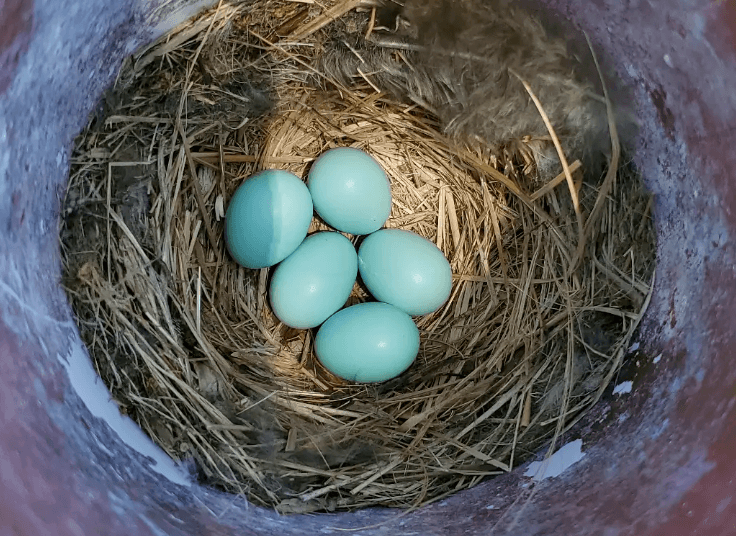

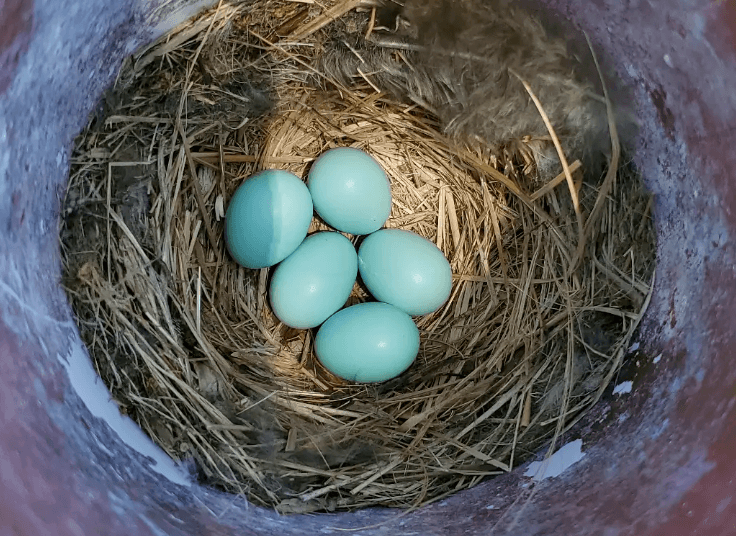

Monitors learn how to ID the nests and eggs of common cavity nesters so that they can determine who is using the box. Blue birds build a grass nest and their eggs are blue.

Mouse nests, wasps, and invasive house sparrow nests must be removed. It is illegal to disturb an active nest of any native bird without a permit so if another species is using the box, leave it be.

Once the eggs hatch, nestling bluebirds will stay in the nest for about 15 days. After day 12 the box should not be opened because the nestlings may fledge early. Once the fledglings are gone, the nest can be removed, allowing more bluebirds to potentially use the box.

Monitoring a nestbox trail is a great way to participate in supporting native species. Visit the North American Bluebird Society website to learn more about how to get started!

Resources: